Wonders of Scotland and Ireland. 10

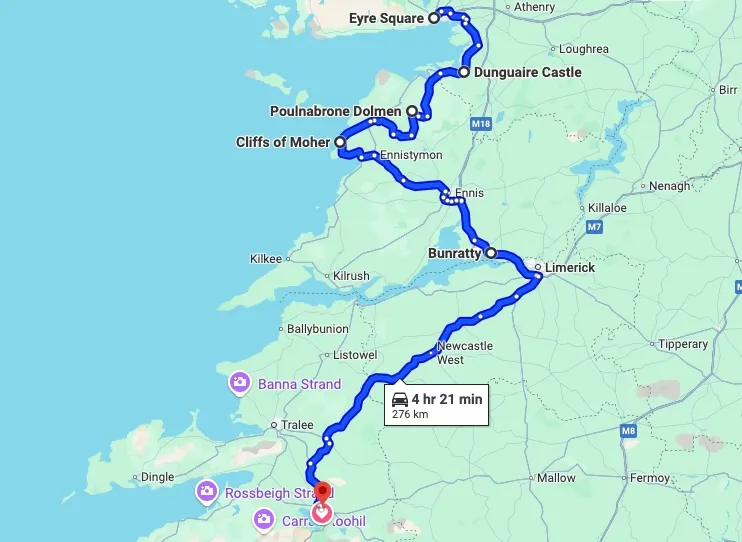

Day. 10 Galway, Burren, Cliffs of Moher, Bunratty and Killarney

Day1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12

Dunguaire Castle: A Modest Castle with Mighty Stories

Ah now, you haven’t seen proper Ireland ‘til you’ve taken the spin down from Galway to Kinvara, and caught sight of Dunguaire Castle, standing there like a proud old fella with his toes in the sea and his back to the wind — defiant, a bit weathered, and not one bit bothered.

It’s the kind of place you drive past and immediately pull the car over — not because there’s parking (there isn’t), but because it demands a bit of your attention, and rightly so.

Built in 1520 by the O’Hynes clan, the place is named after King Guaire of Connacht, who reigned back in the 7th century and was known for being so generous that the food would fly off his plate before he’d get a bite — headed straight to someone more in need. Now that’s charity for you. If Guaire were around today, the man would have nothing left but an empty bowl and a smile.

The castle later fell into the hands of the Martyns, one of Galway’s famous Fourteen Tribes — the kind of folks who drank wine from Spain, traded silk and spices, and probably wouldn’t look twice at a spud unless it was wrapped in lace.

But Dunguaire’s real party piece came a few hundred years later during the Irish Literary Revival. The place became a kind of highbrow shebeen for the likes of W.B. Yeats, Lady Gregory, and George Bernard Shaw — all gathered round the hearth, reading poems, arguing about Irishness, and trying to outdo each other with big ideas and small teacups. Sure, you wouldn’t be surprised if a few ghosts still linger, quoting lines and rolling their eyes at tourists.

These days, you can attend a medieval banquet inside the castle — a grand affair with flagons of mead, roast beef the size of your head, and actors declaiming Irish myths like it’s a pub session in Valhalla. There’s music, candlelight, and a great whiff of nostalgia in the air. It’s all good fun — and for a moment, you’ll believe you’re back in Guaire’s court yourself, just waiting for the roast chicken to levitate.

So, if you’re ever roaming west and see a tower house peering out over Galway Bay, do yourself a favour: stop the car, stretch the legs, and tip your hat to Dunguaire — where the stones tell stories and even the ghosts might offer you a bowl of stew… if King Guaire hasn’t given it away first.

After a further drive of about thirty minutes, we make our way into the surreal and karst landscape of The Burren to discover one of Ireland's 175 portal dolmens ..

Poulnabrone Dolmen: Ritual, Power, and the Stark Beauty of The Burren

To approach Poulnabrone Dolmen, rising solemnly from the limestone terraces of The Burren, is to enter not merely an ancient necropolis, but a ceremonial landscape that pre-dates the written word, monarchies, and indeed, even the concept of Ireland itself.

Situated in County Clare, atop the unyielding karst of the Burren, this megalithic tomb — dating to circa 3800–3200 BC — is among the oldest extant monuments on the island. Yet, to simply describe it as “Neolithic” or “prehistoric” is to obscure its deeper resonance. Poulnabrone is no primitive folly. It is a purposeful structure, meticulously assembled from stone slabs, intended to elevate the dead both physically and symbolically above the living world.

Its name, Poll na Brón, translates — quite evocatively — as “the hole of the sorrows.” And sorrow it most certainly entombs. Excavations in the 1980s revealed the remains of over twenty individuals, including infants, children, and adults — each carefully interred with objects of significance: polished stone axes, shards of pottery, and pendants of bone. This was not mere burial; it was ritualised veneration, implying a society with deeply ingrained spiritual and hierarchical structures.

But it is the surrounding landscape — the Burren — that truly amplifies the significance of this dolmen. The Burren is unlike anywhere else in Ireland. A lunar expanse of fissured limestone pavement, criss-crossed with clints and grikes, it presents a visual paradox: desolate, yet blooming. Here, Arctic, Mediterranean, and Alpine flora coexist with baffling tenacity. This botanical anomaly suggests a civilisation in intimate dialogue with its environment — attuned to its harshness, yet not dominated by it.

What is often overlooked is that the Burren, in its day, would not have been as barren as its name suggests. Recent palaeoecological studies indicate it once supported woodland, grazing, and small farming communities — a network of clan-based societies likely bound by kinship and religious observance. That they chose this windswept plateau for their most sacred rites speaks to a kind of deliberate theatre of death, in which natural drama reinforced ancestral power.

It is telling that Poulnabrone Dolmen is frequently photographed in silhouette — stark against a dramatic sky — echoing our fascination not just with what it was, but what it represented: the origins of social order, of memory, of monumentality.

To dismiss it as merely “ancient” is to ignore its modern function. It continues to serve as a monument, as a metaphor, and, crucially, as a mirror. For here lies one of Ireland’s oldest truths: that even in the most apparently inhospitable places, life was cultivated, honoured, and ultimately memorialised with a sophistication that still humbles us today.

Driving on the winding country roads of the Burren by way of Lisdoonvarna we make our way 45 minutes latter to the Cliffs of Moher

Day1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12

The Cliffs of Moher: A Living Edge on the Wild Atlantic Way

Rising solemnly from the waves of the Atlantic Ocean, the Cliffs of Moher are a place where nature’s power is laid bare — raw, elemental, and profoundly humbling. Here, along Ireland’s fabled Wild Atlantic Way, the land does not simply meet the sea — it confronts it.

Stretching for some eight kilometres along the coast of County Clare, and reaching heights of over 214 metres, the cliffs offer a spectacle of geological drama and unrelenting beauty. Standing upon their edge — wind in your face, gulls wheeling above — one senses the enormity of natural time. These sedimentary layers of shale and sandstone, formed over 300 million years ago, speak to an ancient seabed uplifted and sculpted by the same restless ocean that still carves it today.

This is a place not only of stark geological grandeur, but also of immense ecological importance. Nestled within the crevices of the cliffs are over 20 species of seabirds, including Ireland’s largest mainland colony of Atlantic puffins, whose colourful beaks and comical expressions belie their prowess as agile fliers and skilled fishers. Guillemots, razorbills, kittiwakes, and fulmars wheel and cry in great colonies — their calls swallowed by the roar of wind and surf.

The cliffs also serve as a rare coastal stronghold for peregrine falcons, the fastest creatures on Earth, which can be seen hurtling along the cliff faces in pursuit of prey. Below, the Atlantic churns with life — bottlenose dolphins, basking sharks, and even the occasional minke whale trace the currents along this marine corridor.

And then, among the heather and windswept grass, stands a curious human addition: O’Brien’s Tower, built in 1835 by local landowner and MP Cornelius O’Brien. Far from a medieval relic, this Victorian-era folly was constructed — somewhat romantically — as a viewing point, so that 19th-century visitors might appreciate the vistas as we do today. O’Brien, an eccentric and progressive landlord, believed that tourism could transform the economic fortunes of the area. In this, he was something of a visionary.

From the summit of the tower, on a clear day, one can see as far as the Aran Islands, the Twelve Bens of Connemara, and the misty headlands of Loop Head. But often, it is the cloud and sea spray that dominate — shrouding the cliffs in an ethereal veil and adding to their mysterious allure.

And this is perhaps the cliffs’ most profound gift: they allow us to feel small — not diminished, but awakened. Here, standing on the lip of the continent, where land yields to ocean and sky, we are reminded of our place in a living, breathing world far older and far wilder than ourselves.

The Cliffs of Moher are not simply a viewpoint, or even a landmark. They are a living edge — a theatre of time and tide, of species and stone, whispering the ongoing story of Earth itself.

An hour's drive East through County Clare, via Ennistymon, Ennis, and passing by Shannon, will take us to Bunratty Castle.

Day1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12

Bunratty Castle: A Fortress of Kings and Revival

Set against the pastoral charm of County Clare, just a short drive from Shannon Airport, Bunratty Castle stands as one of Ireland’s most authentically restored medieval strongholds. Rising proudly from the banks of the River Ralty, it bears silent witness to centuries of clan rivalry, colonial conflict, aristocratic grandeur, and eventual cultural revival.

🏰 A Fortress with Ancient Roots

The name Bunratty comes from the Irish Bun Raite, meaning “the mouth of the Ralty” — the small river that flows into the Shannon Estuary nearby. While the current stone castle dates to 1425, the site has seen continuous human settlement since at least the 9th century, when Viking traders established a base here to control the rich waterways of the west.

Before the existing castle was built, there were at least three earlier fortresses on the site — wooden and earthwork structures that rose and fell with the fortunes of Gaelic and Norman power. These early strongholds were largely destroyed in warfare, notably during the upheavals of the 13th and 14th centuries.

🛡️ The O’Brien Dynasty: Kings of Thomond

The most famous custodians of Bunratty were the O’Brien clan, direct descendants of Brian Boru, the High King of Ireland who defeated the Vikings at Clontarf in 1014. By the 15th century, the O’Briens had consolidated their power in the west and were crowned Kings of Thomond — a Gaelic realm roughly equivalent to modern-day Clare, Limerick, and parts of Tipperary.

It was Maccon Sioda O’Brien, the clan’s ruling chieftain, who commissioned the current stone castle around 1425. More than a military outpost, Bunratty was intended as a powerful symbol of Gaelic authority — a fusion of fortress and noble residence, with grand banqueting halls, private apartments, and defensible towers.

In the 16th and 17th centuries, the O’Briens’ political role evolved under English pressure. The family converted to Anglicanism and were granted the English title of Earls of Thomond, effectively embedding them within the British aristocracy. Despite this realignment, they retained a strong connection to Gaelic identity and local tradition.

🏗️ Architectural Features

Bunratty Castle is a classic tower house, a type of fortified dwelling common in Ireland during the late medieval period. The structure rises over four storeys, with massive limestone walls, corner turrets, and murder holes designed for defence. The main entrance leads into a vaulted great hall with a minstrel’s gallery, from where guests would have dined beneath tapestries, chandeliers, and hunting trophies.

From the battlements, one can still gaze across the same fertile plains and tidal estuary that made this such a strategic site for centuries.

🎩 Decline and Restoration

By the 18th century, Bunratty Castle had fallen into ruin. The O’Briens had moved to more fashionable Georgian homes and the castle itself was abandoned, its roof collapsed, its stonework exposed to the elements.

This might have been its fate — like so many other Irish castles left as romantic ruins — were it not for Lord Gort, a 20th-century Anglo-Irish aristocrat with a deep love for history. In 1954, Lord Gort (Standish Vereker, the 6th Viscount Gort) purchased the crumbling remains and meticulously restored the castle to its 15th-century grandeur.

Lord Gort’s vision extended beyond bricks and mortar. He assembled a rich collection of 16th- and 17th-century furniture, tapestries, and artefacts from across Europe to recreate the authentic feel of a Gaelic stronghold. In a lasting gesture, he gifted Bunratty Castle to the Irish state, helping secure its place as a national monument and cultural treasure.

🎭 Living History

Today, Bunratty Castle & Folk Park draws visitors from around the world. Daytime tours explore its storied halls, while medieval banquets—complete with costumed performers, harpists, and flagons of mead—revive the convivial spirit of the great Gaelic chieftains.

The surrounding folk park, created as part of the restoration, reimagines 19th-century rural Ireland with thatched cottages, farmhouses, a schoolhouse, and traditional crafts — offering an immersive journey into Irish heritage.

🏰 Bunratty Castle: A Visual and Historical Portrait

The towering walls and crenellated parapets you see in these images are no mere aesthetic—they are the enduring legacy of the O’Brien clan, ruling as Kings of Thomond, who transformed Bunratty into a seat of Gaelic authority from the early 16th century. Later, under Henry VIII’s “surrender and re‑grant” scheme, the O’Briens became Earls of Thomond, adopting Anglicanism while retaining their local power and commissioning improvements like the lead roof and Great Hall extensions under Donogh O’Brien and successors.

The castle’s placement at the mouth of the River Ratty (hence Bun Raite) reflects deliberate strategy—a site of continuous occupation since the Vikings and a stronghold through medieval clan rivalry. The structure you see was largely completed by the MacNamara chieftains, with the O’Briens assuming control around 1500 and establishing Bunratty as their principal seat, moving from Ennis.

By the mid-17th century, during the Confederate Wars, Barnabas O’Brien, 6th Earl of Thomond, controversially admitted an English parliamentary garrison into the castle, only to see it besieged by Confederate Irish forces and permanently lose the O’Brien residence. His departure marked the end of native clan rule here.

After centuries of decline—used at times by the Studdert family and even as an RIC barracks—the castle fell to ruin. That was until Lord Gort, an Anglo-Irish noble and antiquarian, bought the site in the 1950s. With support from John Hunt and archaeologist Percy le Clerc, he meticulously restored the castle and refurnished it with 16th- and 17th-century tapestry, furniture, and art. In a generous national gesture, Lord Gort donated it to the Irish State, ensuring its survival as a cultural monument. Since then, visitors worldwide are welcomed to medieval banquets in the Great Hall, bringing the history alive.

📜 In Summary

Bunratty Castle is far more than just a picturesque ruin. It is a testament to Irish resilience and reinvention — the stone embodiment of Gaelic kingship, colonial adaptation, and modern cultural pride. From the O’Briens of Thomond to Lord Gort’s visionary revival, this castle continues to speak across the centuries to those who walk its echoing halls.

We now have a 2-hour drive to Killarney in County Kerry and should arrive before 6pm

Day1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12

Go to Day 11