Wonders of Scotland and Ireland. 12

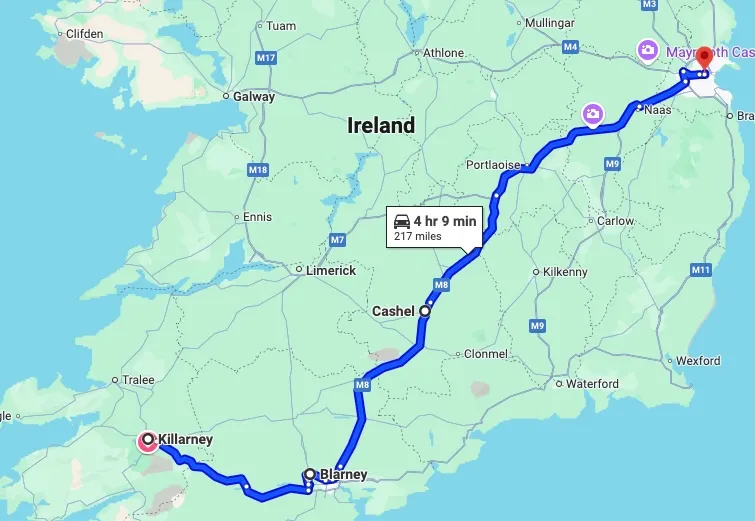

Day 12 Killarney to Blarney, The Rock Of Cashel and then Dublin

Day1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12

Killarney to Blarney: Through Mountains, Memory, and the Gift of the Gab

Leaving Killarney, that jewel of Kerry whose lakes and mountains have been immortalised in watercolour and song, the N22 takes you northeastward. At first, the road runs through gentle valleys, wooded and lush, with the long ridge of the MacGillycuddy’s Reeks still in sight behind. But soon, as you pass through the Irish-speaking village of Ballyvourney — a place where the Gaelic tongue lingers as tenaciously as the scent of peat smoke — the land begins to rise.

Ahead lie the Derrynasaggart Mountains, a rugged but modest range straddling the Cork–Kerry border. The road threads between their slopes, past conifer forests and open heath, with the radio mast of Mullaghanish standing sentinel on the heights. It is a landscape that feels caught between two worlds: the softness of Kerry behind, the firmer, more deliberate country of Cork ahead.

Macroom and the Echoes of Conflict

Descending into the valley of the River Lee, the road brings you to Macroom — a market town that has seen more than its share of history. At its heart stands the castle gateway, the sole survivor of the MacCarthy stronghold that once dominated this bend in the river. In 1650 it was seized by Admiral William Penn under Cromwell’s authority; later, in the 1920s, it bore witness to the convulsions of Ireland’s fight for independence.

Indeed, only a few miles away lies the site of the Kilmichael Ambush (28 November 1920), where Tom Barry’s West Cork IRA column destroyed a patrol of British Auxiliaries. That battle, fought with ruthless determination, was both a tactical victory and a grim warning that Ireland’s struggle was reaching a decisive pitch. A roadside monument marks the site — a stark granite reminder that the road you travel today was once a theatre of war.

Leaving Macroom, the Derrynasaggart Mountains recede into the western haze, their granite bones giving way to the rich farmland of the Lee Valley. The river itself, broad and unhurried here, accompanies you eastward — a pastoral companion on the next stage of your journey.

From Macroom to Blarney: A Road Winding into Legend

The N22 carries you toward Ballincollig, where Cork’s suburban fringe begins to nibble at the hedgerows. But before the city swallows you whole, you turn northward, taking the R617 through Tower and Kerry Pike. The traffic thins, the air feels fresher, and hedgerows give way to glimpses of stone walls and pasture.

And then, quite suddenly, the object of your pilgrimage appears: the battlemented silhouette of Blarney Castle, rising from its wooded parkland. You pass through the village green — neat, inviting, and anchored by the famous Woollen Mills — before following the drive into the castle grounds. Here, the tarmac gives way to gravel paths, and the modern road’s hum fades into birdsong and the rustle of leaves.

You are not simply arriving at a tourist site. You are stepping into the domain of the MacCarthy Mór, into a legend that has somehow managed to entangle Gaelic resilience, Tudor exasperation, and one particularly famous stone.

Day1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12

Blarney Castle: Stone, Story, and the Subtle Art of Evasion

The site was fortified long before the present tower rose in the mid-15th century. An earlier structure — probably a smaller stone fort — gave way in 1446 to the current keep, built by Cormac Láidir MacCarthy, lord of Muskerry and a branch of the ancient MacCarthy Mór dynasty, Kings of Desmond. The design was typical of Irish tower houses: tall, narrow, and massively built, its walls up to 18 feet thick — both a symbol of lordly prestige and a fortress against sudden attack.

Elizabeth I, the MacCarthy Mór, and “Blarney” as a Word

In the late 16th century, Queen Elizabeth I sought to tighten her grip on Ireland. The MacCarthy Mór of the day — generally identified as Cormac Teige MacCarthy — was commanded to surrender his castle. Cormac replied with a masterclass in deferential delay: courteous letters, promises of compliance, and vague assurances, yet not an inch of stone was yielded.

Elizabeth, a monarch well-versed in political fencing, is said to have declared in frustration that his fair words were “nothing but Blarney” — that is, flattering speech utterly devoid of action. The word stuck, and so did the Irish delight in turning an English insult into a badge of honour.

The Legend of the Blarney Stone

The castle’s other great claim to fame is the Blarney Stone, set into its battlements. Legends of its origin abound:

- a fragment of the ancient Lia Fáil coronation stone from Tara;

- a gift from Robert the Bruce after Bannockburn in 1314;

- or, most enchantingly, the reward of a witch who instructed Cormac Láidir to kiss the stone for the gift of eloquence.

Whatever the truth, the stone now lies in a position requiring both nerve and contortion to kiss. Visitors must lie on their backs, lean out over a drop (mercifully protected by rails), and plant a kiss on the underside. Whether or not it truly grants eloquence, it has certainly bestowed upon Blarney an enduring fame.

Day1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12

Later History and Romantic Ruin

The 17th century brought confiscation and partial dismantling of the castle after the Williamite wars. Though its walls endured, the roofless keep was left to ivy and rain. In the 18th and 19th centuries, however, Romanticism made ruins fashionable, and Blarney became a favoured destination for artists and travellers seeking the picturesque.

Blarney House and the Gardens

In 1874 the Colthurst family, owners of the estate, built Blarney House — a Scottish Baronial fantasy of turrets and gables overlooking the lake. The Colthursts still reside there, and its interiors remain a time capsule of Victorian elegance.

The surrounding gardens are a blend of formality and whimsy. The Rock Close presents a druidic landscape of ancient yews, megalithic-looking stones, and the Wishing Steps, where one must climb backward with eyes closed to seal a desire. The Poison Garden, more recent, bristles with wolfsbane, mandrake, and other toxic beauties, reminding visitors that not all gifts of nature are benign.

Blarney Today

Today, Blarney Castle is ruin, legend, and garden combined — a place where medieval walls frame Victorian fantasy, and where visitors of every nationality queue to kiss a stone in pursuit of a gift as old as rhetoric itself. Whether or not the magic works, one leaves with a story to tell. And that, perhaps, is the real Blarney — a tale so well told that it scarcely matters if it’s true.

Heading North from County Cork, we head for County Tipperary - and yes, it's a long way to go! - Well, about an hour and a half.

We'll stop for about 20 minutes for a photostop and comfort break

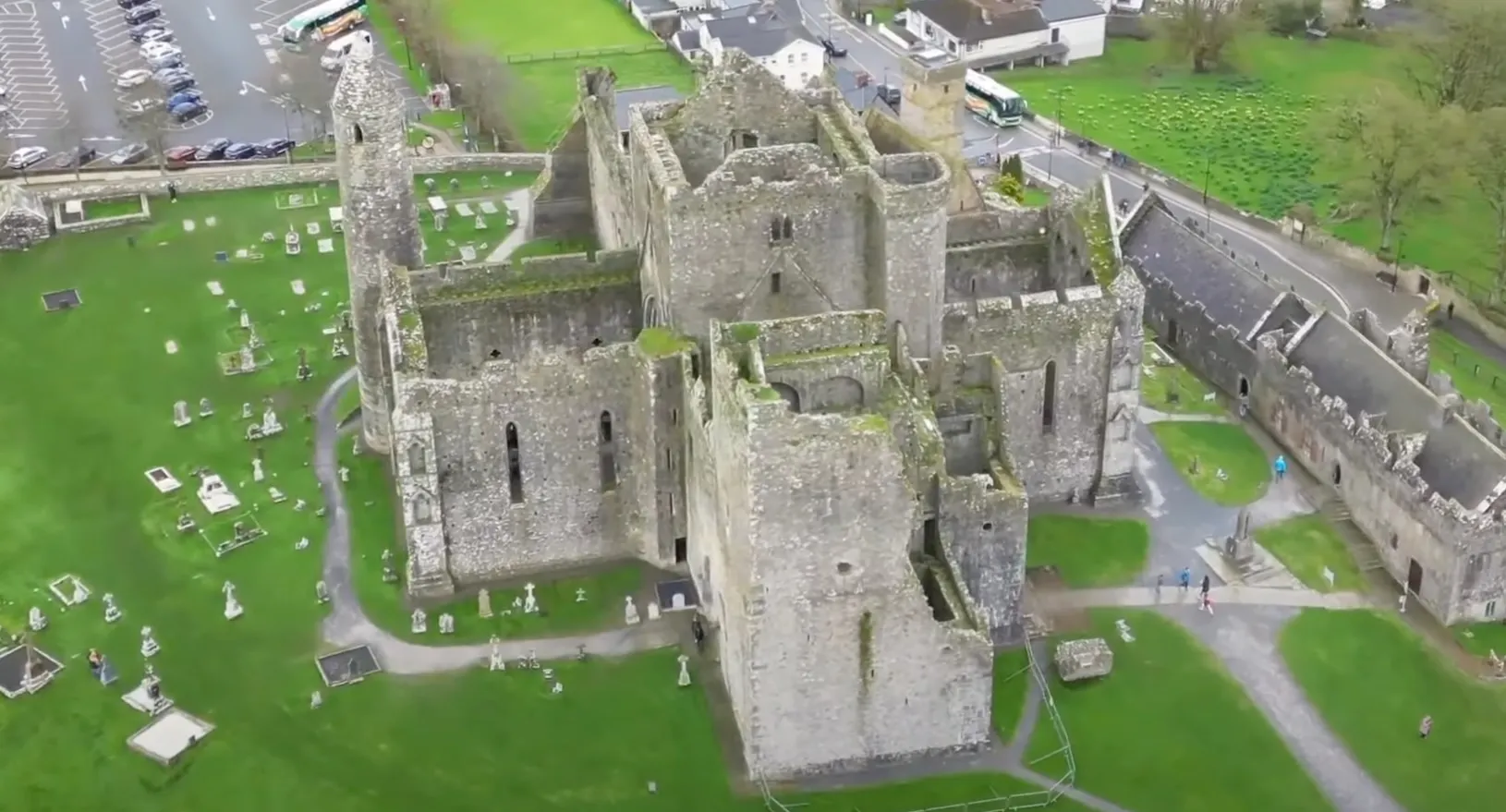

The Rock of Cashel: Crown of Munster

Rising abruptly from the fertile plain of Tipperary like a ship out of an emerald sea, the Rock of Cashel commands instant attention. This great limestone outcrop — 200 feet high and sheer-sided — has for over a thousand years been both fortress and symbol, seat of kings and shrine of saints. From the moment it catches the eye, one sees why the ancient kings of Munster chose it as their capital: it is at once unassailable and spectacular.

The Legend

Local legend insists the Rock’s origins are supernatural. Long ago, St. Patrick was said to be confronting the Devil at the nearby Devil’s Bit mountain. In his fury, Satan bit a chunk out of the mountain and spat it across the valley — where it landed in Tipperary, forming the Rock of Cashel. St. Patrick himself is said to have visited here in the 5th century, baptising King Aengus of Munster. According to tradition, the saint’s crozier pierced the king’s foot during the ceremony; Aengus, thinking it part of the ritual, bore the pain without complaint — an act of devotion that would have impressed even the sternest medieval chronicler.

The History

Historically, Cashel was the seat of the Eóghanachta dynasty, rulers of Munster, from at least the 4th century until the 12th. Here Brian Boru, Ireland’s most famous High King, was crowned in 978. In 1101, King Muirchertach Ó Briain gifted the Rock to the Church, removing it from the blood-stained squabbles of secular power.

The ecclesiastical complex that grew thereafter became one of Ireland’s greatest religious centres. Its most iconic structures include:

- Cormac’s Chapel (1134), a jewel of Hiberno-Romanesque architecture, its sandstone walls carved with chevrons and grotesques.

- The Round Tower (c.1100), soaring 28 metres and visible for miles — the oldest surviving building on the site.

- The Cathedral (13th century), a roofless Gothic shell whose pointed arches and lancet windows frame the sky.

- The Hall of the Vicars Choral (15th century), later restored for use as a heritage centre.

Cashel remained a major religious site until the 17th century, when it was sacked by English Parliamentarian forces in 1647 during the Irish Confederate Wars — a massacre that marked the end of its active ecclesiastical life.

The 20-Minute Stop: What to See from the Car Park

If time is short — and the lure of the open road strong — even from the car park and its immediate approaches you can absorb much of the Rock’s drama.

- The Approach View: Standing by your vehicle, look up at the sheer limestone base crowned by the jagged silhouettes of towers, gables, and battlements. The combination of the round tower, the Gothic cathedral’s east window, and the square bulk of Cormac’s Chapel is the Rock’s classic profile — a layered history in stone.

- Panoramic Vistas: Turn away from the Rock and take in the Golden Vale — a rich quilt of fields, hedgerows, and farmsteads, stretching toward the distant Galtee Mountains. On a clear day, this is one of Ireland’s most idyllic pastoral scenes.

- The Cathedral Gables: Even from outside the ticketed area, you can often see into the open nave of the great cathedral through its tall windows, framing sky instead of stained glass.

- Cormac’s Chapel Roofline: Spot the steeply pitched roof of the chapel, its sandstone hue a warmer contrast to the greyer limestone of the other buildings.

- The Graveyard Slopes: The outer slopes are studded with Celtic crosses and weathered headstones — stark against the green, they make fine photographs with the Rock towering above.

With a camera in hand and a keen eye, those 20 minutes are enough to capture the essence of Cashel: a fortress of kings turned citadel of faith, now a romantic ruin surveying the richest farmland in Ireland.