Wonders of Scotland and Ireland. 9

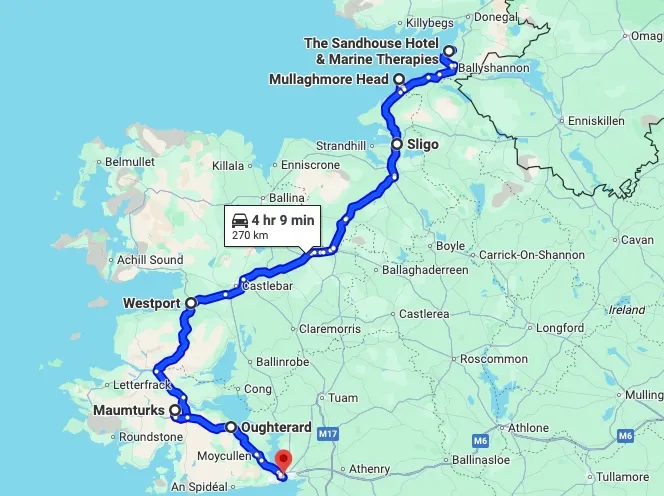

Day 8: From Donegal, Mullaghmore, Sligo, Westport, Connemara to Galway City.

Day1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12

This journey from Rossnowlagh to Galway threads together natural wonders, literary landmarks, tragic histories, and cultural highlights. From Classiebawn Castle’s golden sandstone silhouette, through Yeats’s grave under Benbulben, to the spire of Galway Cathedral beside the Corrib’s steady flow, every moment offers something memorable.

Tucked into a windswept corner of County Sligo on Ireland’s northwestern coast, Mullaghmore is a breathtaking headland known for its dramatic Atlantic views, golden beaches, and the imposing silhouette of Classiebawn Castle. Today, this stretch of the Wild Atlantic Way is a haven for surfers and travelers chasing panoramic scenery, but it is also marked by one of the most tragic events in modern Irish history: the assassination of Lord Louis Mountbatten in 1979.

Classiebawn Castle: Solitary and Striking

Classiebawn Castle, standing sentinel over Mullaghmore, is one of Ireland’s most recognizable private residences. Designed in the 19th century in the Scottish Baronial style, it was commissioned by Lord Palmerston, a British Prime Minister, and completed decades later by his descendants. The castle’s striking sandstone walls, turreted tower, and gabled roofs are set dramatically against Benbulben Mountain, making it a landmark visible for miles.

Although it resembles a medieval fortress, Classiebawn was always intended as a summer retreat for the British aristocracy. In the mid-20th century, it became the Irish home of Louis Mountbatten, 1st Earl Mountbatten of Burma — a prominent British naval officer, statesman, and last Viceroy of India.

Lord Mountbatten and the 1979 Tragedy

Mountbatten was a beloved figure in both royal and political circles, an uncle to Prince Philip and mentor to Prince Charles. Each summer, he brought his family to holiday at Classiebawn. He was known locally not only for his high-profile status but for his friendly demeanour, often seen around the harbour chatting with fishermen or taking his boat, the Shadow V, into the bay.

But on August 27, 1979, that idyllic summer routine ended in horror. As Mountbatten set out on a fishing trip from Mullaghmore Harbour, a bomb planted by the Provisional IRA exploded aboard his vessel. The blast killed Mountbatten, his 14-year-old grandson Nicholas Knatchbull, a local boy named Paul Maxwell, and the Dowager Lady Brabourne. Several others were badly injured. The assassination was intended as a political statement during the Troubles — a stark reminder that even the most peaceful corners of Ireland were not immune to violence.

The tragedy sent shockwaves through Britain and Ireland, and made global headlines. Many locals were devastated, having known Mountbatten as a neighbour rather than a symbol of the British establishment.

Mullaghmore Today

Today, Mullaghmore is a place of haunting contrasts. Its sheer cliffs and Atlantic breakers attract big wave surfers from around the world, while walkers trace the headland loop for uninterrupted ocean views. A memorial stone near the harbour quietly commemorates the victims of 1979, set against the timeless beauty of sea and sky.

Despite its painful past, Mullaghmore is a place of reflection, resilience, and peace. The castle remains privately owned and is not open to the public, but its silhouette is etched in the landscape — and in memory.

In Mullaghmore, history lives in the wind, the waves, and the quiet gaze of Classiebawn over the Atlantic.

Day1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12

Drumcliff: Where Yeats Lies Under Benbulben’s Watch

Nestled beneath the brooding presence of Benbulben, a table-top mountain with mythic stature in Irish folklore, lies the quiet village of Drumcliff, County Sligo. Though modest in size, Drumcliff draws global visitors for a singular reason: it is the final resting place of William Butler Yeats, one of Ireland’s most revered poets.

Yeats’s connection to Sligo is deep and personal. Though born in Dublin, he spent childhood holidays in the nearby town of Rosses Point and later immortalized Sligo’s landscape in his poetry. For Yeats, this region was not just a backdrop — it was the soul of his imagination.

The heart of Drumcliff is St. Columba’s Church, built in 1809, with its steeple piercing the sky. In the adjoining graveyard lies Yeats’s grave, marked by a simple limestone headstone bearing the iconic epitaph from his poem Under Ben Bulben:

“Cast a cold eye / On life, on death. / Horseman, pass by.”

These lines reflect Yeats’s stoic philosophy and his wish for anonymity in death. Visitors often stand quietly, absorbing the powerful stillness of the scene. Behind the grave, Benbulben rises like a timeless sentinel, just as Yeats envisioned.

Nearby stand remnants of Drumcliff’s older past — an early Christian round tower, part of a monastic settlement founded by St. Columba in the 6th century, and a well-preserved Celtic high cross, carved with intricate Biblical scenes.

Though tranquil, Drumcliff resonates with layers of meaning — poetry, spirituality, and landscape, bound in harmony.

Day1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12

Sligo Town: Yeats’s Heartland and Gateway to the Wild Northwest

Sitting at the mouth of the Garavogue River and surrounded by ocean, mountain, and myth, Sligo Town is a place where poetry and history ripple through everyday life. Though often overlooked for Ireland’s more tourist-saturated cities, Sligo quietly holds its own, offering a perfect blend of culture, charm, and coastal energy.

Its name comes from the Irish Sligeach, meaning “abounding in shells,” referencing the shell middens left by early coastal inhabitants. The town has been a trading hub for centuries — a fact reflected in its medieval port and the Georgian buildings that line its narrow streets.

But above all, Sligo is Yeats Country. W.B. Yeats spent much of his youth here, and the landscapes — from Lough Gill to Knocknarea — recur throughout his work. The poet once wrote:

“The place that has really influenced my life most is Sligo.”

Today, literary echoes linger in the town’s bookstores, galleries, and pubs. The Yeats Society Building, located near Hyde Bridge, is home to a permanent exhibition, and each summer the Yeats International Summer School draws scholars and poetry lovers from around the world.

History, too, is written in Sligo’s stones. The atmospheric Sligo Abbey, founded in 1253, is one of the finest medieval ruins in Ireland. Its Gothic arches and preserved high altar offer a glimpse into a time when friars walked the cloisters. Even more haunting are the stories of the abbey’s survival through rebellion, reformation, and Cromwellian destruction.

The town’s fishing and maritime legacy is tangible along the quayside, where boats still moor in the shadow of the Glasshouse Hotel, a modern landmark of glass and steel that contrasts with Sligo’s older architecture. Just beyond lies the scenic Garavogue Riverwalk, where swans glide past mossy stone bridges and street musicians echo the artsy undercurrent of the town.

Culturally, Sligo punches well above its weight. Its vibrant arts scene is supported by venues like The Model, an arts centre and gallery housed in a restored 19th-century building, where exhibits blend modern creativity with nods to local heritage. Live traditional music spills from pubs like Shoot the Crows and Hargadon’s, where you might hear fiddlers playing into the small hours.

Day1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12

Westport: Graceful Streets and Pirate Legends on Clew Bay

Set against the backdrop of Croagh Patrick and facing the island-dotted waters of Clew Bay, the town of Westport, County Mayo, is one of Ireland’s most picturesque and historically rich towns. Built with a deliberate Georgian elegance, Westport is more than just visually pleasing — it’s a living reflection of Ireland’s layered past.

The story of Westport begins with an unlikely figure: Gráinne Mhaol, or Grace O’Malley, the legendary 16th-century pirate queen of Connacht. Her stronghold once stood at the mouth of the Carrowbeg River, where the town now lies. Known for her maritime skill and unshakable defiance of English rule, Grace O’Malley commanded a fleet from Clew Bay and is said to have met Queen Elizabeth I without bowing — a symbolic meeting of two powerful women from opposite worlds.

The modern town, however, owes much to the Browne family, descendants of Grace O’Malley. In the 18th century, they commissioned the celebrated architect James Wyatt to design a planned town on the river, moving the old settlement away from its original location near Westport House. Wyatt’s design introduced an elegant, symmetrical layout of tree-lined boulevards, graceful bridges, and stone terraces — a vision that still defines the town’s aesthetic today.

At the heart of Westport lies The Mall, a green riverside promenade lined with lime trees, walking paths, and period buildings. It leads naturally to Westport House, the ancestral home of the Brownes, built partially on the foundations of Grace O’Malley’s original castle. The house itself is a treasure trove of Irish aristocratic history, with opulent rooms, portraits, and stories of political intrigue, famine aid, and rebellion.

Today, Westport House has opened its grounds and halls to visitors, offering a glimpse into both elite and everyday Irish life across the centuries. The estate is surrounded by sprawling parkland, a lake, and family-friendly attractions, blending history with leisure.

Westport is also known for its vibrant town centre, with its gently sloping streets, colorful shopfronts, and cozy pubs. There’s an unmistakable liveliness to the town — part market bustle, part holiday energy. Traditional music spills from pubs like Matt Molloy’s, owned by the famed flautist from The Chieftains. Artisan cafés and craft shops offer everything from handwoven textiles to local seafood.

But perhaps Westport’s greatest appeal lies in its surroundings. Just a short drive away is the base of Croagh Patrick, Ireland’s sacred mountain, where pilgrims climb to the summit in honour of St. Patrick. To the west, Clew Bay unfolds in a sweep of shimmering water and scattered islands — local lore says there’s one island for every day of the year.

Westport is not only a beautifully designed town — it is a portal into Ireland’s soul. Rich in legend, history, and culture, it offers a tranquil yet vibrant stop along any journey through the west of Ireland.

Day1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12

Leenane: Gateway to Connemara and Harbour of the Hills

Tucked between towering hills and the deep waters of Killary Harbour, the village of Leenane (or Leenaun) is one of Ireland’s most scenically situated settlements. Perched right on the border of Counties Galway and Mayo, this tiny but unforgettable village is the unofficial eastern gateway to Connemara — a region defined by wild beauty, misty mountains, and a pace of life untouched by the frantic energy of modernity.

Leenane sits at the innermost tip of Killary Fjord, Ireland’s only true fjord, a glacially carved inlet that stretches 16 kilometres to the open Atlantic. The village is flanked by the rugged Maumturk Mountains to the south and the imposing Mweelrea, Connacht’s highest peak, to the north. In every direction, the land seems to rise and fall in vast, unspoiled sweeps of granite, bog, and heather.

The surrounding area has long been known for its deep cultural roots and striking scenery. The Connemara ponies — small, hardy, and famously sure-footed — are native to this region. You’ll often see them grazing on roadside grass or wandering near the slopes, a symbol of the relationship between people and land that defines this landscape.

In fact, Connemara itself, whose boundaries are more cultural than administrative, has long been viewed as Ireland in its rawest form. The Irish language (Gaeilge) is still spoken by locals in some of the surrounding areas, and traditional music, storytelling, and crafts remain a way of life.

Despite its quiet nature, Leenane has had its moments in the spotlight. The village and surrounding area famously served as the primary filming location for Jim Sheridan’s 1990 film “The Field,” starring Richard Harris. The stark hills and stone-walled fields captured on screen perfectly matched the film’s themes of land, loss, and memory — themes that still resonate deeply in rural Ireland.

Leenane is also a haven for those seeking outdoor adventures. Boat tours depart regularly from the harbour, offering serene voyages along the fjord with views of waterfalls, mussel farms, and perhaps even dolphins. Hiking and cycling routes fan out into the valleys and over the hills, and trails like the Western Way allow for deeper immersion into the natural terrain.

In the heart of the village, visitors can enjoy homemade meals, browse local crafts, or learn about regional history at the Sheep and Wool Centre, which explores the role of sheep farming and wool production in Connemara’s past.

Day1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12

Connemara: The Untamed Soul of the West

To journey into Connemara is to step into a world shaped more by myth and mountain than by modern life. Stretching from the edge of Leenane to the Atlantic shores of Clifden and beyond, Connemara is not merely a region of County Galway — it is a deeply poetic idea: a place where Ireland’s raw, unfiltered essence still breathes in the heathered hills, low stone walls, and mist-draped boglands.

Bounded by the Twelve Bens mountain range to the north and the Atlantic’s edge to the west, Connemara is a mosaic of elemental forces. Mountains sweep down into rust-colored valleys, bogs shimmer with silver pools, and the sky itself seems impossibly vast—constantly shifting in mood and colour. This is not the neatly green Ireland of postcards, but a wilder, more dramatic landscape where light and weather dance in minutes, and solitude is more abundant than sound.

The name Connemara comes from Conmhaicne Mara, meaning “descendants of the sea.” It’s a fitting origin, given how much of this land is shaped by water — not only by the roaring Atlantic and intricate inlets of the coast, but by the thousand lakes and winding rivers that lace the region.

A defining feature of Connemara is its Gaeltacht status — an area where Irish (Gaeilge) is still spoken as a first language. This linguistic heritage preserves not just vocabulary but also values, rhythms of thought, and a living connection to Ireland’s precolonial culture. Local place names — like Casla, Carna, or Ros Muc — are ancient, rooted in landscape and legend.

Culturally, Connemara is a powerhouse. It’s the home of sean-nós singing, an unaccompanied, deeply emotional vocal tradition that seems to emerge from the land itself. The Connemara Pony, native to the region, is world-renowned for its agility, strength, and gentle temperament. These ponies — descended from hardy native breeds and perhaps even shipwrecked Spanish horses from the Armada — roam freely in many areas, embodying the spirit of independence and resilience that defines the west.

For visitors, Connemara offers more than scenery. Kylemore Abbey, nestled beneath the slopes of Duchruach Mountain, is one of Ireland’s most romantic sights — a neo-Gothic castle turned Benedictine monastery, mirrored in the still waters of a lake. The nearby Inagh Valley provides one of the country’s most breathtaking drives, threading between the Maumturks and Twelve Bens in a golden corridor of bog and rock.

Galway City: Heart of the West, Soul of the Sea

Perched on the edge of the Atlantic, where the River Corrib spills into Galway Bay, Galway City is a place where time moves to a rhythm all its own — swift and salty like the sea breeze, yet also steeped in the shadows of ancient stone. Known affectionately as “The City of the Tribes,” Galway is both a cultural capital and a coastal stronghold — equal parts medieval port town, bohemian haven, and living museum.

To truly understand Galway, one must begin with its foundations — not just physical, but familial. The term “City of the Tribes” refers to the 14 merchant families who dominated the city’s political and commercial life from the late medieval period until the Cromwellian conquest. These families — names like Lynch, Joyce, Browne, and D’Arcy — were primarily of Anglo-Norman descent. They established Galway as a thriving trade hub during the 13th to 17th centuries, building its fortunes on shipping, commerce, and tight-knit political control.

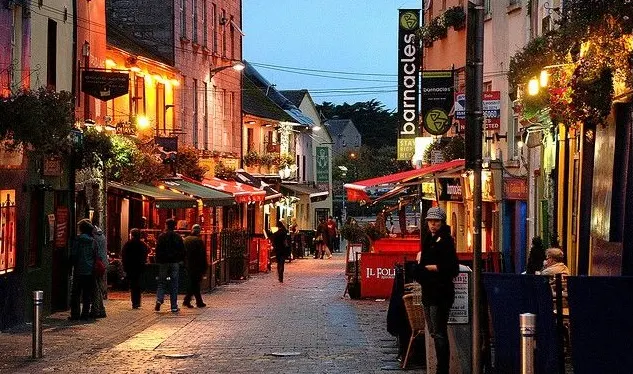

Their legacy can still be felt today in the architecture and layout of the city. Stroll down Shop Street, Galway’s main pedestrian thoroughfare, and you walk in the footsteps of traders, sailors, and nobility. Medieval townhouses, stone-clad shopfronts, and the echoing arcades of Lynch’s Castle (now a bank) speak to a time when Galway was one of the most fortified and self-contained cities in Ireland.

Trade was Galway’s lifeblood, and its links to Spain were particularly strong. During the height of its mercantile power, Galway was seen as Ireland’s most “continental” city. Spanish wines, silks, and spices arrived through the harbour, while Galway exported fish, wool, and leather. These connections were not merely commercial — they were cultural, architectural, and occasionally romantic. Many Galway families intermarried with Spanish merchants, and the term “Spanish Arch,” which still stands today near the Corrib, hints at these enduring ties.

Perhaps the most dramatic chapter in this maritime relationship came in 1588, when ships of the Spanish Armada, fleeing English pursuit and treacherous storms, wrecked along Ireland’s west coast. Survivors were sheltered — and sometimes executed — depending on the local lord. In Galway, there are tales of shipwrecked sailors being buried in the region, with their influence said to linger in dark hair, olive skin, and local surnames.

Despite these cosmopolitan ties, Galway remained fiercely Irish. During the Reformation and English occupation, the city suffered siege, famine, and forced land redistribution. Yet, even in hardship, it retained a rebellious and artistic spirit. The Irish language has long held strong in this region, particularly in the surrounding Connemara Gaeltacht, and Galway’s musicians, writers, and performers have always reflected a culture both ancient and ever-evolving.

Today, that spirit is alive in every corner of the city.

Walk through the Latin Quarter and you’ll find stone-paved streets brimming with energy. Cafés hum with conversation, artists sketch in alcoves, and buskers play traditional tunes on fiddles and flutes. There’s a sense of spontaneity to Galway — a city where music isn’t reserved for stages, but spills into alleys and over pints of Guinness. Annual events like the Galway Arts Festival, Galway Races, and Galway International Oyster Festival draw visitors from around the world, but the vibrancy is year-round.

Then there’s the river — the Corrib, one of Europe’s shortest but fastest-flowing rivers. It divides the city, surges beneath stone bridges, and flows past NUIG (University of Galway), where generations of writers and scholars have studied under sea-lit skies. Swans float past the weir, and fly fishermen still cast their lines in spring and summer, a gentle nod to traditions unchanged by centuries.

A walk along the Claddagh Basin takes you to the heart of Galway’s fishing heritage. The Claddagh, once an independent village, was home to generations of fishermen who lived by a code of their own. The famous Claddagh ring, with its hands, heart, and crown symbolising friendship, love, and loyalty, originated here. Today, jewellers across the world reproduce its form, but its soul belongs to Galway.

Rising above the west side of the city stands one of its most commanding and sacred landmarks: Galway Cathedral. Completed in 1965, it may seem relatively modern by Irish standards, but its presence is monumental. Built on the site of the former city jail, the cathedral incorporates Renaissance, Romanesque, and Gothic styles, with a stunning green dome, intricate mosaics, and Connemara marble floors. It represents not only faith but also transformation — the reclaiming of a place of punishment into one of peace.

For those who prefer quiet exploration, the Eyre Square green offers a central place to pause. Surrounded by pubs, shops, and statues — including one of John F. Kennedy, who visited Galway shortly before his death — it captures the city’s blend of tradition and vitality. From there, it’s just a short walk to the old city walls, the Hall of the Red Earl, or the remnants of medieval gates, all speaking to a time when Galway guarded itself from external influence, even as it welcomed the riches of the world through its port.

Galway is also a base for exploring further west: the Aran Islands, Connemara, and the Cliffs of Moher are all within reach, making it both a destination and a doorway.